Gene-editing treatment approved by Health Canada for sickle cell disease and thalassemia was tested in St. Paul’s Hospital clinical trial

A gene editing treatment for sickle cell disease (SCD) and transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia (TDT) has received marketing authorization from Health Canada, following the results of a first-in-Canada clinical trial that took place in part at St. Paul’s Hospital.

Innovation | Grace Jenkins

A gene editing treatment for sickle cell disease (SCD) and transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia (TDT) has received marketing authorization from Health Canada, following the results of a first-in-Canada clinical trial that took place in part at St. Paul’s Hospital.

The treatment was tested in two global clinical trials. St. Paul’s Hospital was one of four active Canadian sites for the TDT-focused trial, along with BC Children’s Hospital, the Hospital for Sick Children, and Toronto General Hospital.

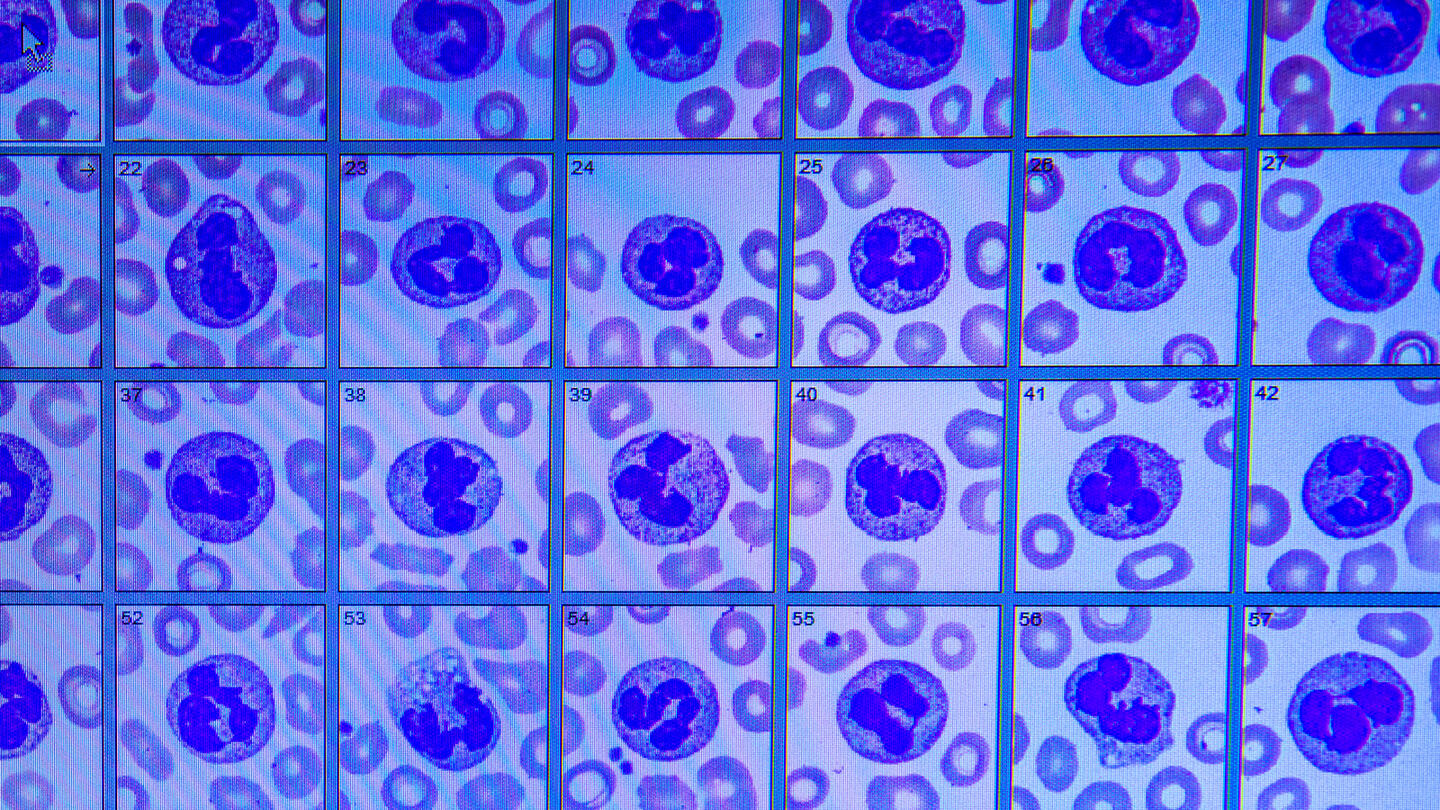

Digital image of whole blood slides used to identify and count red cells, white cells and platelets.

“It’s been really exciting to be a part of this clinical trial for new therapeutics,” says Dr. Hayley Merkeley, the principal investigator of the St. Paul’s Hospital clinical trial. Dr. Merkeley, a hematologist, is the medical director of St. Paul’s Adult Red Cell Disorders Program, which serves nearly 400 adult patients in BC and the Yukon living with SCD and thalassemia.

SCD and TDT significantly impact patients’ quality of life

SCD and TDT are genetic blood disorders that affect how oxygen is carried through the body. Both conditions can have serious complications, impacting patient’s quality of life and requiring lifelong treatment.

SCD causes misshapen or "sickled" red blood cells, causing severe pain, organ damage and shortened life span. Thalassemia is a rare disorder that causes a shortage of red blood cells. Its most severe form, TDT, requires patients to receive regular blood transfusions. Many patients with SCD and TDT come from vulnerable patient populations, and historically there has been a lack of research dedicated to these conditions.

St. Paul’s Hospital’s Role in clinical trial

The follow-up trial, led by Dr. Merkeley, looked for any potential long-term side effects and tested the durability of the treatment. The trial is ongoing and will continue clinically assessing patients at regular intervals for fifteen years after treatment.

Emily Lee, a patient living with TDT who participated in the clinical trial, would originally visit St. Paul’s Hospital every three months to have blood work done and check in with Dr. Merkeley about how she was doing. She also had a yearly bone marrow biopsy and MRI to assess her degree of iron overload. Now that she is further along in her follow-up period, her assessments occur every six months.

New data from the follow-up clinical trial was published at this year’s American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition.

Clinical Trial participant Emily Lee